Failing to see Mt Fuji from Hakusan's separate mountain

Was it really necessary to get up two hours before daylight? I may have been rash enough to put the question to the Sensei over our pre-dawn cup of coffee. “You’ll see,” was all she said.

Soon after daybreak, we were walking up through a shadowy forest. The sun had yet to climb over Chiburi-one, the ridge we were heading for. Now I was beginning to understand the early start – geographically speaking, Bessan may be only an appendage to the Hakusan massif. Yet, as the name suggests, it is a “separate mountain”, and to climb it, you need to raise yourself through much the same interval – sixteen hundred vertical metres – as for Hakusan.

In the half-light, the huge trunks rose around us like columns in a Romanesque cathedral. The Sensei pointed out a particularly magnificent tree. It’s a konka, she said. Eh, I asked, what kanji do you spell that with? She gave me a funny look. Ah,

naruhodo, a conker.

We stopped to fill our water bottles at a spring from central casting – a little rill of snow-chilled water, clear as crystal glass, burbling out from under a mossy arch of boulders. No wonder the trees like it here. As we climbed on in the growing light, the giant horse-chestnuts, oaks and katsura gradually gave way to beech trees.

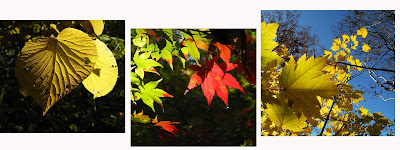

On the ridge proper, we passed through a stand of maple, their leaves backlit a dramatic yellow against the liquid-blue autumn sky. Now we were in the realm of the kōyō, the autumn colours for which Japan’s mountain forests are justly famed.

But – or was this just a nostalgia attack? – perhaps those autumnal ochres and maroons and crimsons weren’t flaring quite as they used to. Stripping off another layer of fibre-pile, I wondered if it was just too warm to start the leaves turning properly.

We sat in a beech grove, sipping the cool water, munching sweet natto, and looking out at the white fringing to Hakusan’s summit crest yonder – yesterday’s clouds must have sprinkled down a little snow, the year’s first.

A clatter of rotor blades cut into our musings – a dun-coloured helicopter, a military spotter, choppered its way up the valley, then circled back. This

hatsu-yuki no longer belonged to us.

Refreshed, we climbed into the realm of the dake-kamba, the rosy-barked high mountain birch. An exposed path led across a flank of the ridge. Fortunately, the black earth of the path was dry. Then suddenly we left the trees and moved up onto a grassy hogsback.

There’s sometimes a large snake here, sunning itself, said the Sensei, whose encounters with the local wildlife include quite a few bear and viper sightings. Privately, I hoped it was too late in the year for such denizens, but you never know your luck in these warming times.

Lunch was taken on a comfortable rock slab beside the refuge hut, some two-thirds of the way up the ridge. Beside the hollow-log water-trough, a sign invited us to clean our boots with the washing-up brushes provided. The idea, it explained, was to stop alien seeds from the lowlands migrating into the alpine zone. Truly, times have changed around here.

Again our musings were interrupted – this time, the whup-whup of rotor blades came from a big Bell helicopter, complete with chin-turret for its gyro-stabilised cameras. Apparently, a visit from NHK. And already the craft was sashaying to and fro across the summit ridge opposite, reeling in footage of the year’s first snow for the evening news show.

When the whine of the twin turbines had died away, we pried ourselves off our sun-warmed slab and turned to the last part of our climb. End-on, the top of Chiburi-one looked almost alpine. Soon our boots crunched through the first shards of ice while, all around, the creeping pine boughs that fringed the path rustled and whispered as they shed last night’s frozen snow.

On the col, a cold wind blew. Taking shelter in a hollow, the Sensei delegated the summit push to me. Ten minutes along the level ridge I came up to a small shrine, fringed with icicles – it’s said that Taichō Daishi, the monk who “opened” Hakusan in that first year of Yōrō (717) also pioneered the Chiburi ridge route to this subsidiary peak.

Beyond a summit marker inscribed with our height – 2,399 metres – the rocky spine of Honshū floated above a blue gulf of low-level haze. My gaze tracked rightwards from the hacksaw serrations of the Northern Alps – yes, there was the pimple of Yari and the statelier domes of the Hodaka massif – across a gap to Ontake, isolated and aloof – and then further still, southwards, to the indistinct ripples of the Chuo Alps.

Those ripples … I wish I’d looked harder in that direction. According to Michio Masunaga in his magisterial book on the mountains of Echizen, an Edo-era scholar named Kuroda Tomoari (1792-1859), who climbed Bessan in search of medicinal herbs, reported that he saw Mt Fuji from here.

Is this really possible?

By consensus, Japan’s highest mountain can’t be seen from the top of Hakusan, fully 300 metres higher than Bessan, because the line of sight is blocked by Ontake. As for Bessan, Masunaga-san says that Mt Fuji would simply be hidden by the earth’s curvature; he himself, in a lifetime of mountaineering, has never seen the mountain from Bessan.

Hoping to settle the question, I later looked at my copy of the

Handbook for Climbing Mt Fuji. Unfortunately, this invaluable reference just muddies matters further - it has a map that suggests that Mt Fuji can indeed be seen from the prefectures of both Fukui and Ishikawa, in which the Hakusan/Bessan massif stands. But, if so, where are those lofty viewpoints?

There was no time to pursue such enquiries now. The Sensei would be freezing in her bower of creeping pine, and we’d better be heading down – the sun was already westering tendentiously towards the Japan Sea.

Sixteen hundred downward metres are hard on the knees. Ours were laughing, as the Japanese say. Yet we managed to keep the sun in the sky until the lowermost woods. Then he dipped below the ridge and we were left darkling. Stars were pricking through the forest canopy by the time we reached the Sensei’s van. There was no need to ask again why we'd got up so early.