In those days, farming villages weren’t distressed as they are today; they were very peaceful places, bustling with people, women too, and in our hill country – although what we spoke of as “mountains” included flat ground with forests and dry fields – we used to go out collecting bracken in spring and mushrooms in autumn. I enjoyed these forays too, although rather more the mountain-climbing than the bracken-harvesting or mushroom-picking. It was probably then that I caught the mountaineering bug.

|

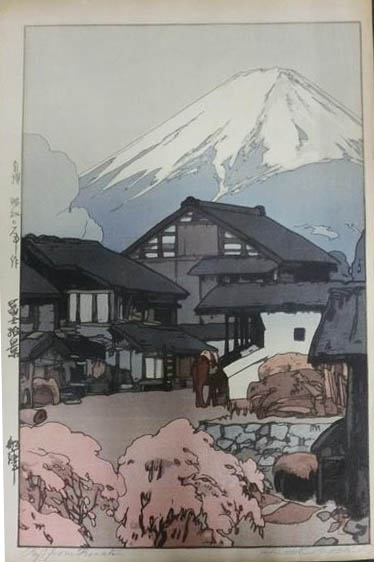

| Village near Mt Fuji: woodprint by Yoshida Hiroshi |

We used to vie with each other in climbing trees on the way home from school. Once I clambered about a hundred feet up a sawtooth oak, and, when I looked down, I saw how small my friends had shrunk to tiny heads with their arms poking out from them, as if their heads were walking by themselves. Then I felt dizzy, and I was too afraid to climb down, so that I had to be rescued by a grown-up. In mountaineering terms, you could say I’d got myself into a pickle.

But I am straying from the subject; the first mountain I ever climbed was Akagi. When I was six, my grandmother took me along to Yu-no-sawa, where she was going to take the waters but, as I don’t remember much except being frightened by stories of tengu, being surprised at the lake on the mountain, and ice being carried away from an icehouse, I doubt if this contributed much to my later love of mountains.

Then, at the age of thirteen, I climbed Mt Fuji. Today, when a nine-year old girl has climbed the mountain and a youngster of eleven can brag about having scaled Ko-Yari, this may not sound particularly novel, but in those days it was almost beyond imagining. There were adherents to both the Fuji faith and the Ontake faith in my village and, as our family belonged to an Ontake congregation, I normally wouldn’t have been allowed to climb the other sect’s Mt Fuji before I’d had the chance to climb Ontake for the first time. But it turned out that another boy of my age was going up Mt Fuji, and I was so envious and made such a fuss that the sendatsu, the Mt Fuji guide, made an exception for me as I was just a child and let me tag along.

|

| Pilgrims on Mt Fuji: woodprint by Yoshida Hiroshi |

As on Ontake pilgrimages, one wasn’t allowed to circumambulate Mt Fuji’s crater on one’s first visit, but I managed to persuade the guide to let me do so, as I was only a child and so it wouldn’t count as a transgression. What I remember fairly well from this trip is the crowds in the mountain huts pressing in on me, eating mochi as the other food was so dreadful, and drinking delicious sweet sake. My memories of the mountain itself have faded to a blur. But the fine mid-August weather held, so that the views were good and you could take in the surrounding mountains with one sweep of the eye. Among them, I remember recognising Akagi when it was pointed out to me, and being delighted when I saw the sea for the first time ever. Also I remember being shocked when I realised that the simple skyline that I saw from my village was, in reality, a much more complicated affair.

What I took away from my Mt Fuji trip was quite simple; that mountain-climbing was very much for me. That is to say, I thought that climbing to high places was for me; it was only much later that I learned to appreciate the true joys of mountaineering. I might grumble that, if only I’d found a proper mentor and undergone the right training, I would have made something of myself as a mountaineer. Anyway, I did discover, by luck more than judgment, that mountaineering was the best way of satisfying that youthful spirit of curiosity and adventure, and that was a feat in itself.

(Continued)